Should a Prosecution Ever Be Private?

By Lean · Dec 01, 2025

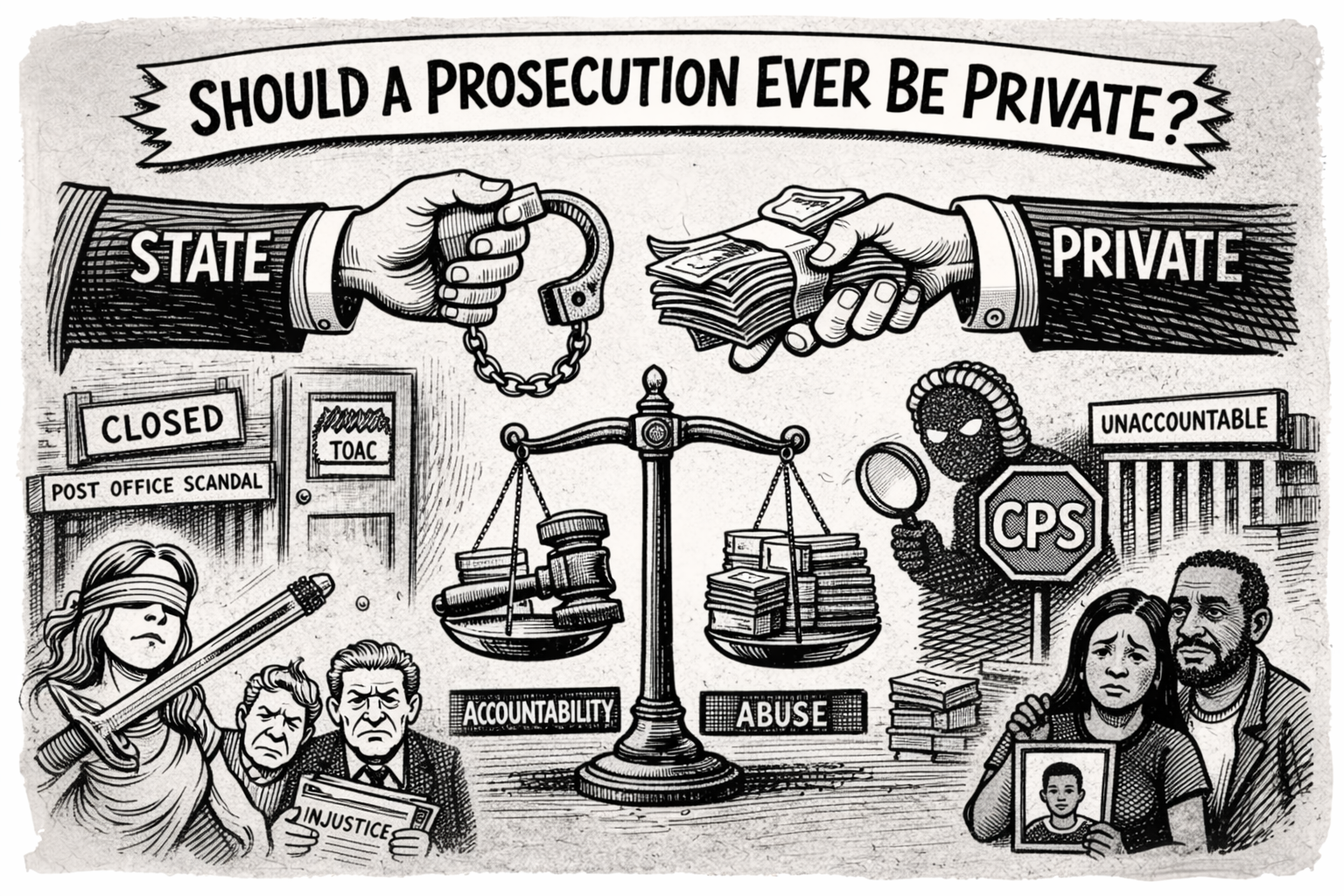

Should a Prosecution Ever Be Private?

Private prosecutions sit uneasily between democratic safeguards and potential abuse. Yet, in a system where the state does not always act, the question arises: should this centuries-old right still have a place?

When the state fails to act, justice can be silenced. The Lawrence family’s 1990s private prosecution, spurred by the CPS's refusal to charge, illustrates the enduring right to citizen prosecutions.

Nearly 40 years after private prosecution was codified, it remains both a lifeline and a legal anomaly, a route to justice when public bodies falter, but one that raises questions about motives and fairness.

This article argues that private prosecutions should remain part of the criminal justice system, but only as a rigorously regulated, exceptional safeguard. Such prosecutions are essential to uphold accountability when state authorities fail to act, provided they operate under robust oversight to prevent abuse.

A Quiet but Powerful Safety Net

Private prosecutions occupy a peculiar role in the criminal justice system. Although the state overwhelmingly controls criminal enforcement, these prosecutions preserve a space for citizens to act when public bodies do not.

The mechanism is simple: anyone can bring a prosecution. The safeguard is equally simple: the DPP can take over and stop it.

Since 2009, that power has been used more actively, aligning private prosecutions with the Crown Prosecutor’s evidential and public interest tests. Notably, cases such as Gouriet (1978) and Gujra (2012) reaffirm that criminal law is ultimately a public function while also confirming that the constitutional right to initiate a case remains intact.

A Democratic Check on State Failure

The Lawrence case remains the clearest example of why the right matters. When the CPS declined to prosecute despite widespread concern, the family’s private action kept the case alive, exposed systemic failures, and helped trigger the Macpherson Inquiry.

Private prosecutions can serve the public interest in situations where policing is compromised, where allegations involve public authorities, where a case carries political sensitivity or where public resources are simply too stretched to act. In such circumstances, the ability of citizens to step in is not an act of confrontation but a constitutional safeguard, a pressure valve in a system that relies heavily on public trust to function.

But Power Can Be Misused

The mechanism is not without dangers. Without institutional oversight, private prosecutions risk becoming tools of harassment, commercial leverage, or personal revenge.

The Post Office Horizon scandal, where a non-state organisation privately prosecuted hundreds of innocent sub-postmasters, illustrates how catastrophic the misuse of this power can be.

Concerns persist about the potential for inconsistent disclosure, significant resource imbalances between parties, weak or untested cases progressing without proper scrutiny, and, ultimately, the emergence of a two-tier justice system in which only those with money or influence can afford to initiate criminal proceedings. If left unchecked, private prosecutions risk undermining the very fairness the criminal justice system is designed to uphold.

Reform, Not Removal

Despite their flaws, private prosecutions form part of the constitutional balance. Therefore, the aim should not be abolition but responsible regulation. Possible reforms include establishing a formal register of all private prosecutors to increase transparency regarding who initiates these cases and the criteria for doing so. Other necessary reforms include clearer disclosure obligations, targeted training and ethical guidance, and routine CPS oversight of serious or sensitive cases.

Lord Diplock’s warning in Gouriet (1978), that private prosecutions safeguard against “capricious, corrupt or biased” failures by public authorities, remains relevant. Public bodies do not always act, and sometimes cannot act. A complete monopoly on prosecution risks closing the door on accountability.

Why It Matters for the Bar

For aspiring barristers, this topic reaches beyond legal doctrine. It touches advocacy ethics, prosecutorial discretion, community trust, and the profession’s role in scrutinising state power.

The future Bar will increasingly encounter questions about who controls criminal justice, how victims access legal remedies, and how the system should respond when public institutions fail. Understanding private prosecutions isn’t merely academic; it is integral to understanding the rule of law itself.

Private prosecutions are imperfect but essential safeguards when the state is silent. Citizens must retain this right, subject to robust oversight.

The power to prosecute should not be monopolised nor used lightly. Done responsibly, private prosecutions support, rather than compete with, public justice.

Lean Sharon